Queer people deserve respect.

It should not be necessary to comprehend queerness to have respect for queer people, but my intention in this post is to present ideas about queerness.

Queer has two primary definitions.

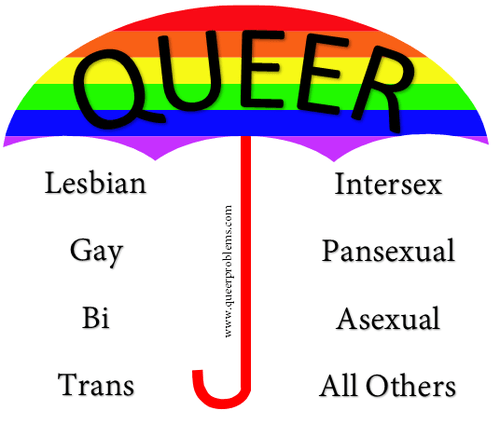

1) Queer is an umbrella term for gender identities that are not cisgender and sexual identities that are not ‘straight.’1

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, pansexual and demisexual are some examples of sexual identities or ‘orientations’ that could be considered queer.

Non-binary, transgender, intersex, gender non-conforming, and gender-fluid are some gender/sex identities included in this definition of queer.

Some people who claim one of these listed identities may not necessarily identify as queer, while others may identify only as queer, or as both gay and queer, bisexual and queer, non-binary and queer, etc.

2) “In other political and academic contexts, ‘queer’ is used…as a term that calls into question the stability of any such categories of identity based on [gender and] sexual orientation.”1

While these two definitions currently coexist, queer as “fluid” and as a critique of human classification can be at odds with certain ideas about gender and sexual identity categories.

There have always been people who today we would refer to as queer, transgender, or non-binary. What has changed is societies’ understanding of bodies and how they function, what social roles and expectations people are compelled to embrace, and the language we use to describe sex, gender, and sexuality. “The Oxford English Dictionary notes that ‘queer’ seems to have entered English in the sixteenth century,” and “by the first two decades of the twentieth century, ‘queer’ became linked to sexual practice and identity in the United States.”1 It was in “the 1940s that ‘queer’ began to be used…primarily to refer to ‘sexual perverts’ or ‘homosexuals,’ most often in a pejorative, stigmatizing way…”1 “The use of ‘queer’ in academic and political contexts beginning in the late 1980s represented an attempt to reclaim this stigmatizing word and to defy those who have wielded it as a weapon.”1 The gay and lesbian liberation movement was foundational for queer social movements that followed, and third-wave feminism is intricately tied with the history of queer theory. In some contexts, and for some individuals, queer can still be incredibly offensive, but it primarily has positive connotations within LGBTIA+ communities today.

To discuss queerness, it is helpful to first explore how sex, gender, and sexuality are interrelated. “In 1972 the sexologists John Money and Anke Ehrhardt popularized the idea that sex and gender are separate categories. Sex, they argued, refers to physical attributes and is anatomically and physiologically determined. Gender, they saw as…the internal conviction that one is either male or female (gender identity) and the behavioral expressions of that conviction.”2 We traditionally think of sex, and the placement of individuals within a binary sex category system3 in terms of scientifically defined traits such as genitalia, chromosomes, gonads, and hormones. People who defend gender essentialism—the belief that gender and sex are binary, fixed, and innate characteristics—often claim allegiance to biology or “science” as central to their belief. However, the concept of binary sex crumbles once you explore history, including the history of biology.

“Early medical practitioners” in the Western world “understood sex and gender to fall along a continuum and not into the discrete categories we use today.” 2 “As biology emerged as an organized discipline during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it gradually acquired greater authority over the disposition of ambiguous bodies. Nineteenth-century scientists developed a clear sense of the statistical aspects of natural variation, but along with such knowledge came the authority to declare that certain bodies were abnormal and in need of correction.” 2 What is considered “normal” versus “abnormal” is a decision based on societal value systems. Furthermore, “[c]hoosing which criteria to use in determining sex, and choosing to make the determination at all, are social decisions for which scientists can offer no absolute guidelines.” 2 This can be demonstrated by the treatment of intersex people by medical professionals.

Intersex individuals are born with sex characteristics that do not fit within the male-female binary and are estimated to represent “1.7 percent of all births.” 2 For comparison, “[a]n estimated 1% to 2% of the general population worldwide has the phenotype for red hair, increasing to between 2% and 6% in the northern hemisphere.”4 In the U.S. and Western Europe, when a newborn has “ambiguous” genitalia, genital surgery is completed9 without parental knowledge or consent.2 Doctors “employ the following rule: ‘Genetic females should always be raised as females, preserving reproductive potential, regardless of how severely the patients are virilized. In the genetic male, however, the gender of assignment is based on the infant’s anatomy, predominantly the size of the phallus.” 2 Western scientists and doctors did not create these standards out of concern for the child’s physiological health, but with the purpose of assigning sex within the society’s binary system, originally presented as necessary for “proper psychosexual development”—which meant making the child and parents “believe” the sex assignment, accept the corresponding gender expectations, and embrace heterosexuality. 2 This history of medical practices and intersex identity reveals the role of individual discretion in sex determination and the interconnection of sex, gender, and sexuality.

While it may be helpful in some discussions to describe sex and gender as distinct, “[t]he more scholars think about the idea of sex versus gender, the clearer it becomes that we are talking about both, knotted together in complex ways.” 2 People who argue against binaries and for acceptance of intersex individuals and queer identity are not discounting biology and physiology. “There are hormones, genes, prostates, uteri, and other body parts and physiologies that we use to differentiate male from female, that become part of the ground from which varieties of sexual experience and desire emerge. Furthermore, variations in each of these aspects of physiology profoundly affect an individual’s experience of gender and sexuality.” 2 For me, queer as an umbrella term and as a critique of scientific and political categorization is about acceptance of the social, historical, biological, physiological, and anatomical realities that bodies and experiences are different. The stories we have been told about gender and sex binaries are not absolute, universal human truths.

Sex determination metrics are one way that sex and gender is “socially constructed,” in that these metrics have changed over time and depend on place and human choice. The gender binary as we know it was an invention—it did not exist prior to the late 15th century and was not a widespread idea in Western society until the 19th century. Before the scientists of the 19th and 20th centuries began to medicalize the body and enforce the gender binary under their authority, it was the political, economic, and legal arena that differing conceptions of gender/sex were discussed. As historian Thomas Laqueur states, “no one was much interested in looking for evidence of two distinct sexes, at the anatomical and concrete physiological differences between men and women, until such differences became politically important.”5 “Distinct sexual anatomy was adduced to support or deny all manner of claims in a variety of specific social, economic, political, cultural, or erotic contexts.”5

Consider the (lack of) gender binary in different cultural contexts. Hijras are transgender and intersex individuals with a distinct gender classification in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Several indigenous cultures from the North American continent also recognized a third gender, sometimes referred to as “two-spirit.” Two-spirit people and “the Hijras vary in their origins and gender characteristics.” 2 This reflects how gender is constructed at the macro level, in terms of accepted systems of classification which differ based on culture.

Gender is also socially constructed at the micro level of face-to-face interaction. Candace West and Don Zimmerman describe gender “as a routine accomplishment embedded in everyday interaction” in their widely acclaimed article “Doing Gender.”3 They state that “[r]ather than as a property of individuals, we conceive of gender as an emergent feature of social situations: both as an outcome of and a rationale for various social arrangements and as a means of legitimating one of the most fundamental divisions in society.”3 Accountability to sex category is central to the concept of doing gender.6 Gender is simultaneously created and enforced as others hold us accountable to gender assumptions and expectations. Consider how gendered ideas about whether a certain type of clothing, a manner of speech or comportment, or an expected labor role only matter when considered in relation to other people. What is considered masculine or feminine is arbitrarily defined. There is no “fixed set of specifications” for gender boundaries.6 They vary based on time, place, and audience.

It is important to understand how “queer” represents opposition to the socially constructed sex and gender binary, but queerness is also about affirmation. Fluidity and the “process” model of embodied gender provide us with more accurate understandings of the development of sex, gender, and sexual identities. To describe this, I will lean heavily on the words of biologist and gender studies scholar Anne Fausto-Sterling. “The model of embodied gender,” which I consider to be both a biological and social scientific conception of queer fluidity, “emphasizes developmental process rather than separate contributing ‘things’ such as genes, hormones, or socialization. Identity is understood as a stable process, not a fixed trait.” 2 Fluidity, in the simplest terms, means the capacity for change. Gender/sex is “a changing river that flows throughout the life cycle.”2 “Rather than being determined at each step by autonomous biological processes, development is an active stasis composed of entangled systems. Change happens if or when something disrupts one or more of the underlying systems, but at any one moment a person’s mindset gives the illusion of fixity.” 2

It is true that “most people always remember having a specific gender/sex identity,” but Fausto-Sterling argues “that they were not born with one, but form a kind of first draft of their identity during the first three years of life, mostly before adult conscious memory becomes established.” 2 Gender/sex is a continuum, and “[b]y definition, a continuum involves gradation; clear categories emerge from cultural practices such as birth certificates, bathroom signs, government identity forms, gender-signaling dress codes, names, etc. In contrast to the idea that, once formed, identity is fixed, a process model envisions identity in terms of relative stability.” 2 The initial rough draft of gender identity we develop represents a period of relative stability, “but stability does not imply permanence.” 2 Is it really so difficult to imagine how this initial draft of identity could change throughout life?

Consider this: “One way the brain ‘hardens’ a neural connection is by producing a fatty sheath, called myelin, around the individual nerve fibers. At birth the human brain is incompletely myelinated. Although major myelination continues through the first decade of life, the brain is not completely fixed even then. There is an additional twofold increase in myelinization between the first and second decades of life, and an additional 60 percent between the fourth and sixth decades, making plausible the idea that the body can incorporate gender-related experiences throughout life.” 2 Our brains change based on our lived experience and the environment in which we live, and our gender and sexuality are important elements of our lived experience.

Gender essentialist, heteronormative beliefs represent one perspective—not the only perspective—of gender and sexuality. Biology, sociology, and history offer us the means to explore other perspectives. “Knowledge about the embryology and endocrinology of sexual development, gained during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, enables us to understand that human males and females all begin life with the same structures; complete maleness and complete femaleness represent the extreme ends of a spectrum of possible body types. That these extreme ends are the most frequent has lent credence to the idea that they are not only natural (that is, produced by nature) but normal (that is, they represent both a statistical and a social ideal). Knowledge of biological variation, however, allows us to conceptualize the less frequent middle spaces as natural, although statistically unusual.” 2 A process-view “does not see cisgender development to be the normal path from which other identities deviate. Instead, a single general process can explain gender/sex identity development in all the forms we know.” 2 Bodies, desires, and identity are unique and have the capacity to change. To generalize and force people into binary gender categories, or force them to embrace heterosexuality, is to deny the full spectrum of human variance.

Widely held ideas about binary gender in popular culture and within scientific study were produced during an era of strict adherence to patriarchy and heteronormativity. Rigid boundaries relating to expressions of masculinity and femininity are absurd restrictions on identity and behavior. “The problem with gender, as we now have it, is the violence—both real and metaphorical—we do by generalizing. No woman or man fits the universal gender stereotype.” 2 To broaden our understanding of gender does not necessarily require “doing away with” gender, though there are folks who are agender. No one is telling you that you cannot identify as a man or woman, or as heterosexual. However, there should be recognition that forcing people within a false binary does incredible harm and upholds social, political, and economic systems of inequality.

There have been more anti-queer bills introduced in U.S. states in 2022 than any year in American history, with most targeting transgender people.7 Progress is not linear. Parents of trans youth are being forced to flee Republican-controlled states. Gender affirming care saves lives. This healthcare is a human right. You are the expert over your body and your identity,8 not a healthcare provider or a politician. We must work to end all forms of violence against queer folks.

Queer freedom is about the freedom to live regardless of where you fit on the continuum of gender/sex. It is the freedom to love who you love. It is about preserving autonomy. It is the freedom to embrace your true self and express yourself openly. It encourages and relies on acceptance and affirmation. Queerness allows for gradation and fluidity. Queer represents freedom from boxes, boundaries, and binaries. Queer freedom does not require any of us to have complete comprehension of the complexity of sex, gender, and sexuality. It only requires respect for variance. In fact, it is simple—queer freedom is about respect for all people.

Sources

1

Somerville, Siobhan B. 2014. “Queer.” Keywords for American Cultural Studies 2:203-207. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1287j69.57

Free PDF: http://985queer.queergeektheory.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Somerville-Queer.pdf

2

Fausto-Sterling, Anne. 2000. Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York: Basic Books.

Purchase: https://www.basicbooks.com/titles/anne-fausto-sterling/sexing-the-body/9781541672895/

3

West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. “Doing Gender.” Gender & Society 1:125-151.

Free PDF: https://www.gla.ac.uk/0t4/crcees/files/summerschool/readings/WestZimmerman_1987_DoingGender.pdf

4

Cunningham, Andrew L., Christopher P. Jones, James Ansell, and Jonathan D. Barry. 2010. “Red for danger: the effects of red hair in surgical practice.” British Medical Journal 341.

https://www.bmj.com/content/341/bmj.c6931

5

Laqueur, Thomas. 1992. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Purchase: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674543553

6

West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 2009. “Accounting for Doing Gender.” Gender and Society 23(1):112-122. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20676758.

Free PDF: https://files.adulteducation.at/uploads/accounting_doinggender__westZimmermann.pdf

7

Branigin, Anne, and Nick Kirkpatrick. 2022. “Anti-trans laws are on the rise. Here’s a look at where — and what kind.” The Washington Post. Retrieved December 19, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2022/10/14/anti-trans-bills/

8

shuster, stef. 2021. Trans Medicine: The Emergence and Practice of Treating Gender. New York: New York University Press.

Purchase: https://nyupress.org/9781479899371/trans-medicine/

9

Blackless, Melanie, Anthony Charuvastra, Amanda Derryck, Anne Fausto-Sterling, Karl Lauzanne, and Ellen Lee. 2000. “How sexually dimorphic are we? Review and synthesis.” American Journal of Human Biology 12:151-166. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(200003/04)12:2<151::AID-AJHB1>3.0.CO;2-F

Featured Image

Creator Unknown. URL: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/sexual-fluidity-and-the-diversity-of-sexual-orientation-202203312717

Umbrella Term Image

Creator Unknown. URL: http://savisyouth.org/differentiation-between-identifying-as-gay-or-queer/

I wanted to keep it simple with the in-text citations. I can provide page numbers for quotes if requested.

Leave a comment